植被物候对极端气候响应及机制

|

张晶(1994-), 女, 黑龙江绥化人, 博士生, 研究方向为植被物候学。E-mail: zhangj1127@mail.bnu.edu.cn |

收稿日期: 2023-06-30

修回日期: 2023-08-20

网络出版日期: 2023-09-28

基金资助

国家自然科学基金杰出青年科学基金项目(42025101)

国家自然科学基金国际合作研究项目(42261144755)

Response of vegetation phenology to extreme climate and its mechanism

Received date: 2023-06-30

Revised date: 2023-08-20

Online published: 2023-09-28

Supported by

National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars(42025101)

International Cooperation and Exchanges of NSFC(42261144755)

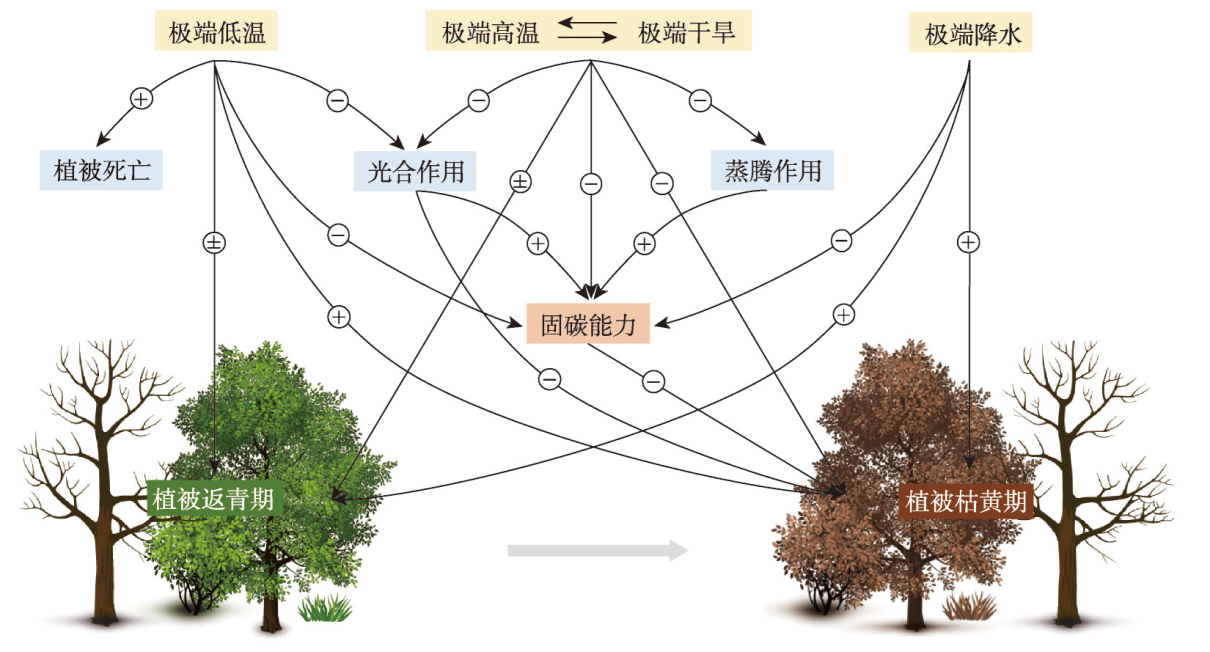

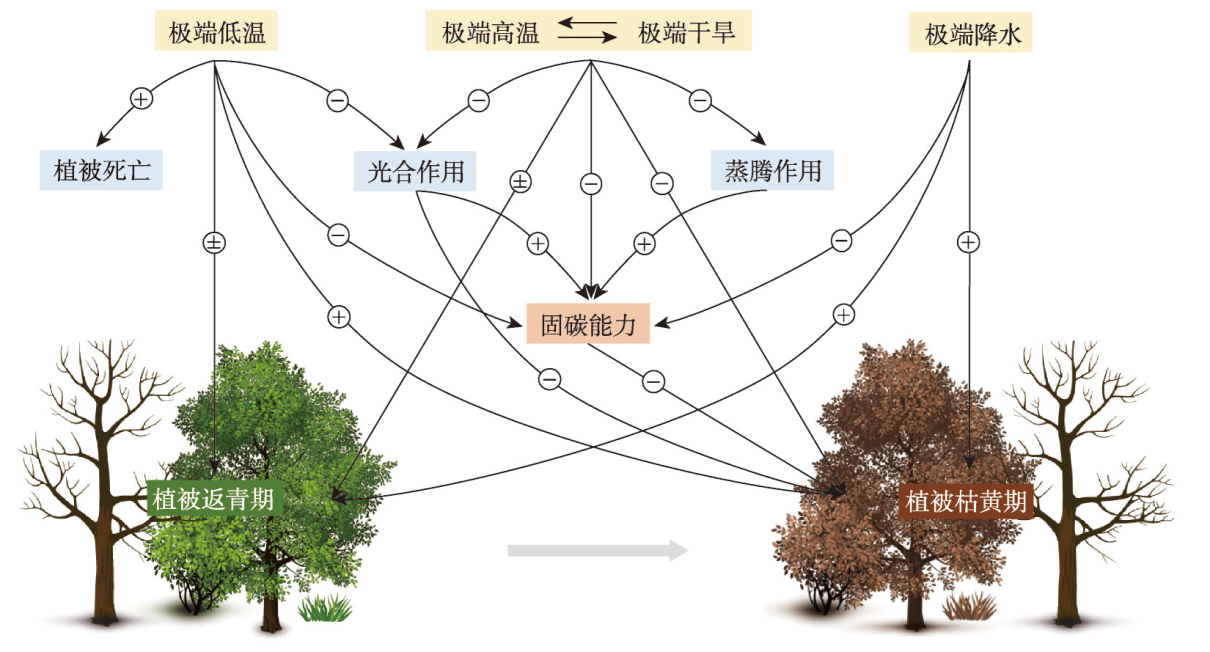

人类活动引起的气候变化导致极端气候事件频发,改变植物的生理过程,影响陆地生态系统碳、水循环和能量平衡。植被物候是气候变化最敏感的生物学指示指标,近年来植被物候对气候变化的响应研究主要关注气候平均态,植被物候如何响应极端气候事件研究相对较少,响应机制仍不清楚。本文梳理了植被春季和秋季物候对各类极端气候事件的响应及其机制,发现北半球中高纬度地区,季前极端低温与极端降水直接导致植被返青期推迟、枯黄期提前,而极端高温和极端干旱导致植物气孔关闭,抑制光合和蒸腾作用,间接导致枯黄期提前。目前植被物候响应极端气候事件研究缺乏对复合极端气候事件的关注,而且植被物候对极端气候响应的滞后效应以及极端气候事件发生后植被的恢复过程研究较少。未来气候变化情景下,需构建考虑极端气候事件影响的植被物候模型,并与动态植被模型耦合,以提高陆地生态系统碳循环的模拟精度。

张晶 , 郝芳华 , 吴兆飞 , 李明蔚 , 张璇 , 付永硕 . 植被物候对极端气候响应及机制[J]. 地理学报, 2023 , 78(9) : 2241 -2255 . DOI: 10.11821/dlxb202309008

Global climate change caused by human activities results in frequent extreme climate events, and shifts the physiological processes of plants, and the carbon, water cycle and energy balance of terrestrial ecosystems. Vegetation phenology is the most sensitive biological indicator to climate change. In recent years, the responses of vegetation phenology to climate change mainly focus on the mean state of the climate, while the response mechanisms of vegetation phenology to extreme climate are still unclear. In this paper, the response of vegetation spring and autumn phenology to various extreme climatic events and their mechanisms were reviewed. We found that extreme low temperature and extreme precipitation directly delayed the vegetation green-up date and advanced the leaf senescence, while extreme high temperature and extreme drought led to stomatal closure, inhibited photosynthesis and transpiration, and thus advanced leaf senescence at middle and high latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere. Currently, the studies on the response of vegetation phenology to extreme climate events pay less attention to compound extreme climate events, and there are only few studies on the lag effect of vegetation phenology response to extreme climate events and the recovery process of vegetation after the occurrence of extreme events. Under future climate change scenarios, it is necessary to modify the vegetation phenological models by considering the impact of extreme climate events and couple it into the dynamic global vegetation models to improve the simulation accuracy of the carbon cycle in terrestrial ecosystems.

表1 干旱等级划分Tab. 1 Classification of drought |

| 分类 | SPEI或SPI | PDSI | 危害程度 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 基本正常 | -0.49~0.49 | -0.99~0.99 | 无危害 |

| 轻旱 | -0.99~-0.50 | -1.99~-1.00 | 轻微危害 |

| 中旱 | -1.49~-1.00 | -2.99~-2.00 | 中等危害 |

| 重旱 | -1.99~-1.50 | -3.99~-3.00 | 严重危害 |

| 特旱 | ≤-2.00 | ≤-4.00 | 特重危害 |

| [1] |

[周贵尧, 周灵燕, 邵钧炯, 等. 极端干旱对陆地生态系统的影响: 进展与展望. 植物生态学报, 2020, 44(5): 515-525.]

|

| [2] |

[朴世龙, 张新平, 陈安平, 等. 极端气候事件对陆地生态系统碳循环的影响. 中国科学: 地球科学, 2019, 49(9): 1321-1334.]

|

| [3] |

IPCC AR6. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

|

| [4] |

|

| [5] |

IPCC. Global Warming of 1.5°C: IPCC Special Report on Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5°C above Pre-industrial Levels in Context of Strengthening Response to Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

|

| [6] |

|

| [7] |

|

| [8] |

|

| [9] |

|

| [10] |

|

| [11] |

|

| [12] |

[竺可桢. 中国近五千年来气候变迁的初步研究. 中国科学, 1973, 3(2): 226-256.]

|

| [13] |

|

| [14] |

[张福春. 气候变化对中国木本植物物候的可能影响. 地理学报, 1995, 50(5): 402-410.]

|

| [15] |

[邓晨晖, 白红英, 高山, 等. 1964—2015年气候因子对秦岭地区植物物候的综合影响效应. 地理学报, 2018, 73(5): 917-931.]

|

| [16] |

[卓莉, 张子彦, 雷小雨, 等. 基于蒙特卡洛生存分析探究东北森林物候的影响因素. 地理学报, 2019, 74(3): 490-503.]

|

| [17] |

|

| [18] |

|

| [19] |

|

| [20] |

|

| [21] |

|

| [22] |

[付永硕, 张晶, 吴兆飞, 等. 中国植被物候研究进展及展望. 北京师范大学学报: 自然科学版, 2022, 58(3): 424-433.]

|

| [23] |

[孔冬冬, 张强, 黄文琳, 等. 1982—2013年青藏高原植被物候变化及气象因素影响. 地理学报, 2017, 72(1): 39-52.]

|

| [24] |

|

| [25] |

|

| [26] |

|

| [27] |

|

| [28] |

|

| [29] |

|

| [30] |

|

| [31] |

|

| [32] |

|

| [33] |

|

| [34] |

|

| [35] |

|

| [36] |

|

| [37] |

|

| [38] |

|

| [39] |

|

| [40] |

|

| [41] |

|

| [42] |

|

| [43] |

|

| [44] |

|

| [45] |

|

| [46] |

|

| [47] |

|

| [48] |

|

| [49] |

|

| [50] |

|

| [51] |

|

| [52] |

[袁沫汐, 赵林, 李鑫鑫, 等. 1982—2015年中国温带不同草地植被枯黄期对极端气候事件的响应. 生态学报, 2023, 43(14): 6015-6032.]

|

| [53] |

|

| [54] |

|

| [55] |

|

| [56] |

|

| [57] |

|

| [58] |

|

| [59] |

|

| [60] |

|

| [61] |

|

| [62] |

|

| [63] |

[龚玉凤, 吴兆飞, 付永硕, 等. 气候变化对北京常见树种春季萌芽的影响: 基于控制实验研究. 生态学报, 2023, 43(5): 1948-1958.]

|

| [64] |

|

| [65] |

|

| [66] |

|

| [67] |

|

| [68] |

|

| [69] |

|

| [70] |

|

| [71] |

|

| [72] |

|

| [73] |

|

| [74] |

|

| [75] |

|

| [76] |

|

| [77] |

|

| [78] |

|

| [79] |

|

| [80] |

|

| [81] |

|

| [82] |

|

| [83] |

|

| [84] |

|

| [85] |

|

| [86] |

|

| [87] |

|

| [88] |

|

| [89] |

|

| [90] |

|

| [91] |

|

| [92] |

|

| [93] |

[张彬, 朱建军, 刘华民, 等. 极端降水和极端干旱事件对草原生态系统的影响. 植物生态学报, 2014, 38(9): 1008-1018.]

|

| [94] |

|

| [95] |

|

| [96] |

|

| [97] |

|

| [98] |

|

| [99] |

|

| [100] |

|

| [101] |

|

| [102] |

|

| [103] |

|

| [104] |

|

| [105] |

|

| [106] |

|

| [107] |

|

| [108] |

[牟成香, 孙庚, 罗鹏, 等. 青藏高原高寒草甸植物开花物候对极端干旱的响应. 应用与环境生物学报, 2013, 19(2): 272-279.]

|

| [109] |

|

| [110] |

|

| [111] |

|

| [112] |

|

| [113] |

|

| [114] |

|

| [115] |

|

| [116] |

|

| [117] |

|

| [118] |

|

| [119] |

|

| [120] |

|

| [121] |

|

| [122] |

|

| [123] |

|

| [124] |

|

| [125] |

|

| [126] |

|

| [127] |

|

| [128] |

|

| [129] |

|

| [130] |

|

| [131] |

[刘凤山, 陈莹, 史文娇, 等. 农业物候动态对地表生物物理过程及气候的反馈研究进展. 地理学报, 2017, 72(7): 1139-1150.]

|

| [132] |

|

| [133] |

|

| [134] |

|

| [135] |

|

| [136] |

[黄文琳, 张强, 孔冬冬, 等. 1982—2013年内蒙古地区植被物候对干旱变化的响应. 生态学报, 2019, 39(13): 4953-4965.]

|

| [137] |

|

| [138] |

|

| [139] |

|

| [140] |

|

| [141] |

[周广胜, 宋兴阳, 周梦子, 等. 植物物候变化的全气候生产要素影响机制与模型研究. 中国科学: 生命科学, 2023, 53(3): 380-389.]

|

| [142] |

|

| [143] |

|

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |