史前人类在青藏高原的定居与动物资源利用

|

王清(1998-), 四川资阳人, 博士生, 主要从事环境考古研究。E-mail: wangqing19@mails.ucas.ac.cn |

收稿日期: 2022-06-02

修回日期: 2022-12-24

网络出版日期: 2023-01-16

基金资助

国家自然科学基金重点项目(41930323)

第二次青藏高原综合考察研究(2019QZKK0601)

Human sedentism and utilization of animal resources on the prehistoric Tibetan Plateau

Received date: 2022-06-02

Revised date: 2022-12-24

Online published: 2023-01-16

Supported by

National Natural Science Foundation of China(41930323)

The Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research Program(2019QZKK0601)

定居是人类从高度移动的游猎生活发展到全年固定于一处居住的漫长过程。定居的发生和发展对人类社会的生产方式、技术演化和文明起源具有深远影响,而定居的产生受到气候变化、人口增长、资源压力、技术革新等多种因素影响。青藏高原是研究人类适应和定居高寒缺氧极端环境的理想区域,对史前人类在青藏高原的定居过程关注较多亦争议颇多。通过梳理已发表的考古学、地理学、遗传学等相关学科文献,发现目前对于史前人类定居青藏高原的研究,侧重于讨论低海拔人群或者农作物扩散的影响,对动物资源在这一过程中的作用则关注较少,定居高原的年代和驱动机制仍存在争议。遗址使用的季节性分析,是判断古人是否全年定居的关键。本文总结了如何利用青藏高原鱼类、鸟类和哺乳类等动物遗存因地制宜进行遗址季节性分析以及建立高原遗址动物资源利用时间表的方法。本文认为,开展史前人类在青藏高原定居与动物资源利用研究,首先,应全面建立和完善青藏高原现生动物骨骼形态、全基因组和蛋白质组的数据库,为考古遗址动物遗存物种鉴定提供基础;其次,在物种鉴定的基础上,研究人—动物—环境之间的关系;最后,评估人类在遗址活动的季节性以及动物资源在人类定居青藏高原过程中的作用。

关键词: 动物考古; 人类适应; 生计模式; 遗址季节性分析; 大批量骨骼宏条形码分析

王清 , 张颖 , 陈顺港 , 高玉 , 杨继帅 , 冉景坤 , 顾政权 , 杨晓燕 . 史前人类在青藏高原的定居与动物资源利用[J]. 地理学报, 2023 , 78(1) : 177 -197 . DOI: 10.11821/dlxb202301012

It is a long process for human to shift from highly mobile to year-round sedentary lifeways. Sedentism had a profound impact on the subsistence, technologies, and ultimately the origin of civilization in human societies. The emergence of sedentism was effected by climate change, population growth, resource pressure, technological innovation and so forth. The Tibetan Plateau is a key region to study human evolution and adaptation to extreme environment due to the alpine and hypoxia conditions. How people adapted and permanently occupied the Tibetan Plateau has been a heated debate in the past decades, but the prehistoric process of sedentism on the Tibetan Plateau is still ambiguous. By reviewing the published archaeological and genetics research, we find that current studies of prehistoric human sedentism on the Tibetan Plateau focused on agricultural diffusion from low-altitude to high-altitude areas and its effects; Few attentions were paid to the role of animal resources in the process of sedentism, and the chronological sequence and driving mechanism of sedentism on the Tibetan Plateau are still controversial. Seasonality analysis is crucial to determine whether a site is occupied year-round. We summarized the methods for seasonality analysis using animal remains, and put forward some suggestions on how to efficiently establish the schedule of animal resources utilization at a site according to the local conditions. Firstly, the database of skeletal morphology, whole genome and proteome of modern animals on the Tibetan Plateau should be established to provide a basis for the identification of animal remains from archaeological sites. Subsequently, the human-animal-environment relationship and the role of animal resources in human sedentism process on the Tibetan Plateau should be evaluated.

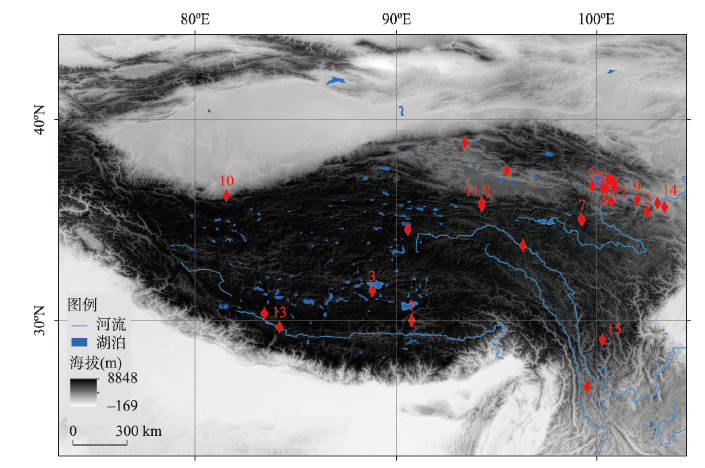

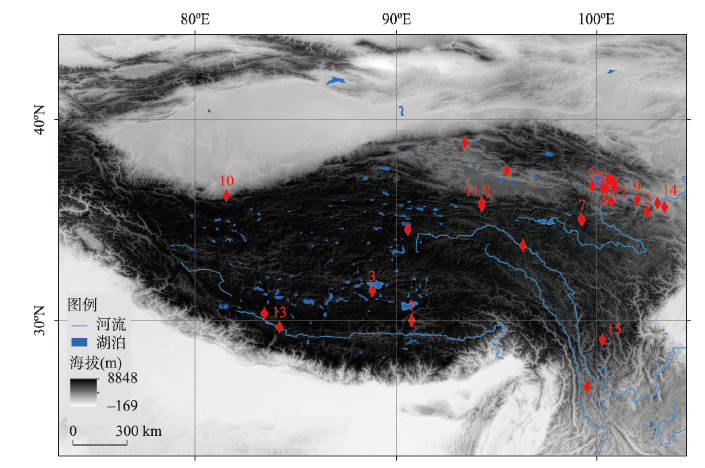

图1 青藏高原旧石器遗址分布注:1. 邱桑(226—169 ka BP、海拔4369 m)[50];2. 白石崖溶洞(190—45 ka BP、海拔3200 m)[48-49];3. 尼阿底;4. 151;5. 江西沟#1;6. 黑马河#1(13.1 ka BP、海拔3200 m)[56];7. 下大武(~11 ka BP、海拔3988 m)[57];8. 西大滩#2;9. 沙隆卡(8.3—8 ka BP、海拔2046 m)[58];10. 羊场(7.6—7.0 ka BP、海拔2440 m a.s.l.)[59];11. 野牛沟(7.5 ka BP、海拔3800 m)[60];12. 拉乙亥(~7.6 ka BP、海拔3125 m)[61];13. 仲巴10-1(6.6—2.6 ka BP、海拔4570 m)[62];14. 奖俊埠01(120—90 ka BP、海拔2673 m)[63];15. 皮洛。 Fig. 1 The distribution of Paleolithic sites on the Tibetan Plateau |

表1 用于批量骨骼宏条形码分析特异性扩增的引物Tab. 1 Primers for specific amplification in bulk-bone metabarcoding |

| 名称 | 序列(5'-3') | 目标 分类群 | 基因片段 | 参考文献 | 扩增长度(bp) | 退火温度(°C) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12SAH | 正向 | CTGGGATTAGATACCCCACTAT | 鸟类 | 12S rRNA | [124] | 229~235 | 57 |

| 逆向 | CCTTGACCTGTCTTGTTAGC | 鸟类 | 12S rRNA | [124] | 229~235 | 57 | |

| Mam16S | 正向 | CGGTTGGGGTGACCTCGGA | 哺乳类 | 16S rRNA | [125] | 89~115 | 57 |

| 逆向 | GCTGTTATCCCTAGGGTAACT | 哺乳类 | 16S rRNA | [125] | 89~115 | 57 | |

| 12S-V5 | 正向 | ACTGGGATTAGATACCCC | 鱼类 | 12S rRNA | [126] | 106 | 58 |

| 逆向 | TAGAACAGGCTCCTCTAG | 鱼类 | 12S rRNA | [126] | 106 | 58 |

表2 青藏高原现生动物线粒体DNA数据完整情况Tab. 2 Completeness of mitochondrial DNA data of living animals on the Tibetan Plateau |

| 类别 | 记录 物种数 | 统计 物种数 | mtDNA数据 | 备注 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 完整 | 部分 | 无 | ||||

| 哺乳类 | 190余 | 149 | 119 | 15 | 13 | 无数据多为蝙蝠科、松鼠科、鼠科和仓鼠科;偶蹄目仅黑麝无完整mtDNA序列 |

| 鱼类 | 159 | 152 | 112 | 20 | 20 | 无数据者在各科均有分布,但同属其他物种多有数据 |

| 鸟类 | 817 | 234 | 152 | 71 | 11 | 无数据多为秧鸡科、鹬科和鸠鸽科、夜鹰科等 |

表3 雅鲁藏布江中游主要鱼类冬夏轮交界处形成时间Tab. 3 The formation time of winter-summer boundary of main fish in the middle reaches of the Yarlung Zangbo River |

| 物种 | 拉丁名 | 冬夏轮交界形成 | 判断 材料 | 参考文献 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 周期(a) | 时间(月份) | ||||

| 双须叶须鱼 | Ptychobarbus dipogon | 1 | 3—5 | 耳石 | [166] |

| 1 | 3—6 | 耳石 | [161] | ||

| 尖裸鲤 | Oxygymnocypris stewartii | 1 | 3—6 3—5 | 耳石 脊椎骨 | [160] |

| 拉萨裸裂尻 | Schizopygopsis younghusbandi | 1 | 3—5 | 耳石 | [167] |

| 黑斑原鮡 | Glyptosternum maculatum | 1 | 4—6 | 脊椎骨 | [162] |

| 异齿裂腹鱼 | Schizothorax o'connori | 1 | 3—5 3—6 | 耳石 脊椎骨 | [163] |

| 拉萨裂腹鱼 | Schizothorax waltoni | 1 | 3—5 | 耳石和 脊椎骨 | [164-165] |

| 巨须裂腹鱼 | Schizothorax macropogon | 1 | 3—6 | 耳石 | [168] |

| 高原裸鲤 | Gymnocypris waddellii | 1 | -- | 臀麟和 背鳍条 | [157] |

| [1] |

|

| [2] |

|

| [3] |

|

| [4] |

|

| [5] |

|

| [6] |

|

| [7] |

|

| [8] |

|

| [9] |

|

| [10] |

|

| [11] |

|

| [12] |

|

| [13] |

|

| [14] |

|

| [15] |

|

| [16] |

|

| [17] |

|

| [18] |

|

| [19] |

|

| [20] |

|

| [21] |

|

| [22] |

|

| [23] |

|

| [24] |

|

| [25] |

|

| [26] |

|

| [27] |

|

| [28] |

|

| [29] |

|

| [30] |

|

| [31] |

|

| [32] |

|

| [33] |

|

| [34] |

|

| [35] |

|

| [36] |

|

| [37] |

|

| [38] |

|

| [39] |

|

| [40] |

|

| [41] |

|

| [42] |

|

| [43] |

|

| [44] |

[ 张镱锂, 李炳元, 刘林山, 等. 再论青藏高原范围. 地理研究, 2021, 40(6): 1543-1553.]

|

| [45] |

[ 郑度, 赵东升. 青藏高原的自然环境特征. 科技导报, 2017, 35(6): 13-22.]

|

| [46] |

|

| [47] |

|

| [48] |

|

| [49] |

|

| [50] |

|

| [51] |

|

| [52] |

|

| [53] |

|

| [54] |

|

| [55] |

|

| [56] |

|

| [57] |

[ 侯光良, 曹广超, 鄂崇毅, 等. 青藏高原海拔4000 m区域人类活动的新证据. 地理学报, 2016, 71(7): 1231-1240.]

|

| [58] |

|

| [59] |

|

| [60] |

[ 汤惠生, 周春林, 李一全, 等. 青海昆仑山山口发现的细石器考古新材料. 科学通报, 2013, 58(3): 247-253.]

|

| [61] |

[ 盖培, 王国道. 黄河上游拉乙亥中石器时代遗址发掘报告. 人类学学报, 1983, 2(1): 49-59, 116.]

|

| [62] |

|

| [63] |

|

| [64] |

[ 郑喆轩, 冯玥, 谭培阳, 等. 四川稻城县皮洛旧石器时代遗址. 考古, 2022(7): 3-14.]

|

| [65] |

[ 陈剑, 曹桂梅, 代堂才, 等. 四川马尔康县哈休遗址2006年的试掘. 南方民族考古, 2010(1): 295-374, 478.]

|

| [66] |

Chengdu Municipal Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, Administration of Cultural Relics of Aba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture, Qiang Museum of Maoxian County. The Yingpanshan Neolithic Site in Maoxian Couty. Beijing: Cultural Relics Publishing House, 2018.

[ 成都文物考古研究院,阿坝藏族羌族自治州文物管理所, 茂县羌族博物馆. 茂县营盘山新石器时代遗址. 北京: 文物出版社, 2018.]

|

| [67] |

Sichuan Provincial Cultural Relics and Archaeology Research Institute, Administration of Cultural Relics of Aba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture, Administration of Cultural Relics of Jinchuan County Archaeology, 2021(3): 16.

[四川省文物考古研究院, 阿坝藏族羌族自治州文物管理所, 金川县文物管理所. 四川金川县刘家寨遗址2011年发掘简报. 考古, 2021(3): 16.]

|

| [68] |

Administration Commission of Cultural Relics of Tibet Autonomous Region. Karuo Site in Chamdo Region. Beijing: Cultural Relics Publishing House, 1985.

[ 西藏自治区文物管理委员会. 昌都卡若. 北京: 文物出版社, 1985.]

|

| [69] |

Heritage Survey Team of Administration Commission of Cultural Relics of Tibet Autonomous Region. Trial excavation report of Xiaoenda Neolithic site in Tibet Autonomous region. Archaeology and Cultural Relics, 1990(1): 28-43.

[ 西藏文管会文物普查队. 西藏小恩达新石器时代遗址试掘简报. 考古与文物, 1990(1): 28-43.]

|

| [70] |

Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Qugong Site in Lhasa. Beijing: Encyclopedia of China Publishing House, 1999.

[ 中国社会科学院考古研究所. 拉萨曲贡. 北京: 中国大百科全书出版社, 1999.]

|

| [71] |

|

| [72] |

|

| [73] |

|

| [74] |

|

| [75] |

|

| [76] |

|

| [77] |

|

| [78] |

|

| [79] |

[ 陈发虎, 刘峰文, 张东菊, 等. 史前时代人类向青藏高原扩散的过程与动力. 自然杂志, 2016, 38(4): 235-240.]

|

| [80] |

|

| [81] |

|

| [82] |

|

| [83] |

|

| [84] |

|

| [85] |

|

| [86] |

[ 陈洪海, 王国顺, 梅端智, 等. 青海同德县宗日遗址发掘简报. 考古, 1998(5): 1-14, 35, 97.]

|

| [87] |

[ 张山佳, 董广辉. 青藏高原东北部青铜时代中晚期人类对不同海拔环境的适应策略探讨. 第四纪研究, 2017, 37(4): 696-708.]

|

| [88] |

[ 吕红亮. 拓殖高原、永久定居、麦作传入: 对当前青藏高原史前考古重大争论的回应. 青海民族研究, 2017, 28(1): 10-13.]

|

| [89] |

|

| [90] |

|

| [91] |

|

| [92] |

|

| [93] |

|

| [94] |

[ 安家瑗, 陈洪海. 宗日文化遗址动物骨骼的研究//河南省文物考古研究所. 动物考古(第1辑). 北京: 文物出版社, 2010: 232-240.]

|

| [95] |

[ 任乐乐. 青藏高原东北部及其周边地区新石器晚期至青铜时代先民利用动物资源的策略研究[D]. 兰州: 兰州大学, 2017.]

|

| [96] |

[ 黄万波. 西藏昌都卡若新石器时代遗址动物群. 古脊椎动物学报, 1980(2): 163-168.]

|

| [97] |

[ 何锟宇, 陈剑. 马尔康哈休遗址出土动物骨骼鉴定报告. 成都考古发现. 2006: 428-440.]

|

| [98] |

[ 何锟宇. 马尔康哈休遗址史前文化与生业: 兼论岷江上游地区马家窑类型的生业方式. 考古, 2015(5): 72-82.]

|

| [99] |

[ 何锟宇, 蒋成, 陈剑. 浅论动物考古学中两种肉量估算方法: 以营盘山遗址出土的动物骨骼为例. 考古与文物, 2009(5): 95-99.]

|

| [100] |

[ 胡松梅, 张建林. 西藏那曲察秀塘祭祀遗址哺乳动物遗存及其意义//河南省文物考古研究所. 动物考古(第1辑). 北京: 文物出版社, 2010: 241-249.]

|

| [101] |

[ 张正为, 夏格旺堆, 吕红亮, 等. 藏北安多布塔雄曲石室墓动物遗存的鉴定分析. 藏学学刊, 2015(1): 1-18.]

|

| [102] |

[ 张正为, 吕红亮. 西藏西部阿里卡尔东遗址2013年试掘出土动物遗存鉴定与分析. 藏学学刊, 2017, 16(1): 252-272.]

|

| [103] |

|

| [104] |

|

| [105] |

|

| [106] |

|

| [107] |

|

| [108] |

|

| [109] |

[ 武云飞, 吴翠珍. 青藏高原鱼类. 成都: 四川科学技术出版社, 1992.]

|

| [110] |

[ 马生林. 青藏高原生物多样性保护研究. 青海民族大学学报(社会科学版), 2004, 30(4): 76-78.]

|

| [111] |

[ 刘廼发, 包新康, 廖继承. 青藏高原鸟类分类与分布. 北京: 科学出版社, 2013.]

|

| [112] |

Tibetan Zoology Compilation Leading Group. The Chorography of Tibet Autonomous Region:Fauna. Beijing: China Tibetology Publishing House, 2005: 588.

[ 西藏动物志编纂领导小组. 西藏自治区志:动物志. 北京: 中国藏学出版社, 2005: 588.]

|

| [113] |

[ 卢欣. 中国青藏高原鸟类. 长沙: 湖南科学技术出版社, 2018: 835.]

|

| [114] |

|

| [115] |

|

| [116] |

|

| [117] |

|

| [118] |

|

| [119] |

|

| [120] |

|

| [121] |

|

| [122] |

|

| [123] |

|

| [124] |

|

| [125] |

|

| [126] |

|

| [127] |

[ 陈炼, 吴琳, 刘燕, 等. 环境DNA metabarcoding及其在生态学研究中的应用. 生态学报, 2016, 36(15): 4573-4582.]

|

| [128] |

|

| [129] |

|

| [130] |

|

| [131] |

|

| [132] |

[ 董斯扬, 薛娴, 尤全刚, 等. 近40年青藏高原湖泊面积变化遥感分析. 湖泊科学, 2014, 26(4): 535-544.]

|

| [133] |

[ 栗静舒, 张双权. 垩质年轮法在旧石器时代动物考古学中的应用. 人类学学报, 2014, 33(2): 177-186.]

|

| [134] |

|

| [135] |

|

| [136] |

|

| [137] |

|

| [138] |

|

| [139] |

|

| [140] |

|

| [141] |

|

| [142] |

|

| [143] |

|

| [144] |

|

| [145] |

|

| [146] |

|

| [147] |

|

| [148] |

|

| [149] |

|

| [150] |

|

| [151] |

|

| [152] |

|

| [153] |

|

| [154] |

|

| [155] |

|

| [156] |

|

| [157] |

[ 杨汉运, 黄道明, 池仕运, 等. 羊卓雍错高原裸鲤(Gymnocypris waddellii Regan)繁殖生物学研究. 湖泊科学, 2011, 23(2): 277-280.]

|

| [158] |

[ 杨汉运, 黄道明, 谢山, 等. 雅鲁藏布江中游渔业资源现状研究. 水生态学杂志, 2010, 31(6): 120-126.]

|

| [159] |

[ 杨汉运, 黄道明. 雅鲁藏布江中上游鱼类区系和资源状况初步调查. 华中师范大学学报(自然科学版), 2011, 45(4): 629-633.]

|

| [160] |

[ 霍斌. 尖裸鲤个体生物学和种群动态学研究[D]. 武汉: 华中农业大学, 2014: 165.]

|

| [161] |

[ 杨鑫. 雅鲁藏布江双须叶须鱼年龄生长、食性和种群动态研究[D]. 武汉: 华中农业大学, 2015: 76.]

|

| [162] |

[ 丁城志, 陈毅峰, 李秀启, 等. 雅鲁藏布江黑斑原鮡的年龄与生长. 中国鱼类学会学术研讨会, 2008.]

|

| [163] |

|

| [164] |

[ 郝汉舟. 拉萨裂腹鱼的年龄和生长研究[D]. 武汉: 华中农业大学, 2005: 51.]

|

| [165] |

[ 周贤君. 拉萨裂腹鱼个体生物学和种群动态研究[D]. 武汉: 华中农业大学, 2014: 128.]

|

| [166] |

|

| [167] |

[ 段友健. 拉萨裸裂尻鱼个体生物学和种群动态研究[D]. 武汉: 华中农业大学, 2015: 137.]

|

| [168] |

[ 刘洁雅. 西藏巨须裂腹鱼个体生物学和种群动态研究[D]. 阿拉尔: 塔里木大学, 2016: 69.]

|

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |